For a few weeks in the early 1980s, I was working short engagement gigs in New York City with a quartet that trumpeter Red Rodney put together. Pianist Walter Bishop, Jr., and drummer Leroy Williams were my colleagues in the rhythm section.

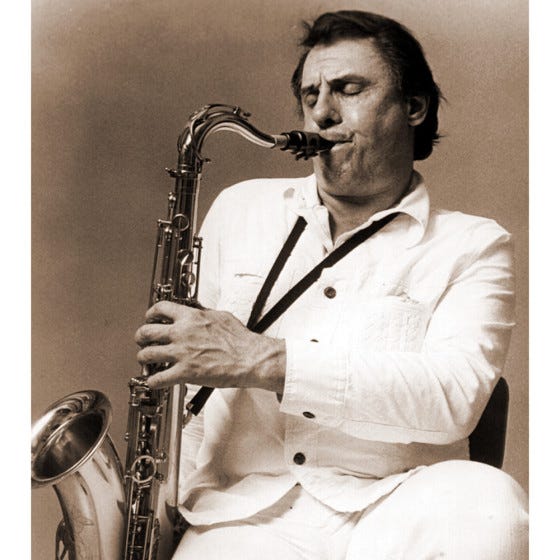

Red Rodney.

We did a few nights here and there at various small joints around town. We never rehearsed, and it was informal. Our repertoire consisted mainly of bebop tunes that Red helped make popular during his time with Charlie Parker in the 1950s. It was a lot of fun, and I was fortunate as a youngster to play with seasoned veterans like these.

(What follows was told to me a couple of years later by a good friend and fellow bassist.)

At the same time, and without my knowledge, multi-instrumentalist Ira Sullivan and Red decided to form a band to tour and record. They contacted pianist Garry Dial and the three of them discussed who to hire for the bass and drummer positions. Red mentioned that he had enjoyed playing with a younger bassist who had recently been doing gigs with his quartet, but he had a mental block at that moment and couldn’t remember my name. Garry Dial asked Red to describe the bassist. Red said he was white, about six feet tall, and had brown hair. Garry asked, “Do you mean Paul Berner?” Red replied, “Yeah, I guess so.”

Ira Sullivan.

The quintet was opening in New York City soon after that, I think it was at the Village Vanguard. They decided to meet there and have their rehearsal a few hours before their opening night. Red had already arrived at the club when the bassist, Paul Berner, arrived. When Red set eyes upon him, he immediately realized that he was not the bassist he intended to recommend (me). But he said nothing, realizing that it was too late to do anything about it. Fortunately, Paul was, and remains, an excellent bassist, and the rehearsal and that week of performances went very well. The band sounded good and everyone was happy.

I guess sometime later, Red let the band know what had happened, but the band was enjoying much success, so it was just one of those things. The next time Paul and I crossed paths, Paul greeted me by saying, “You’re not going to believe this,” and went on to relate the story. Paul and I had a good laugh over it. We were friends who had attended the same University to study music and had somewhat parallel careers.

Paul Berner.

As a result of my not going on the road with that band, I got the call a few weeks later to join Lionel Hampton. That resulted in a couple of years of frequent work, and we travelled all over the world. Had I gotten the gig with Red and Ira, I would likely not have been able to go with Lionel when I did. Happily, this memory slip of Red’s turned out to be good fortune for both Paul and me. I still chuckle about the situation today.

The musicians I have come to know and work with over the past several decades are a dedicated community that has had to work hard and endure the ups and downs of the jazz music business. They are also an immensely talented group of musicians, capable of meeting the demands of the most challenging musical settings. However, the reality is that, regardless of one's dedication and talent, flukes such as the one I have described here do occur. The main thing is for all of us to be in a constant state of readiness, ready for whenever the phone rings and an opportunity comes knocking. It’s one thing to get a gig, no matter how that may come about. It’s an entirely different thing to keep the gig. That is a wholly different matter.

Shakespeare had it right. All’s well that ends well.

TC

Great anecdote. Our lives are so contingent on events beyond our control. Often, we never find out what doors close to us, either when we make a decision, don't make one, or for any other simple twist of fate. I enjoyed Brian Klaas's recent book "Fluke", which makes the point persuasively about the role of chance in our lives.

In a related note, I've long wondered how bandleaders tell their sidemen (or women) that they won't be using them on the next tour, record, whatever. I think I first thought about this years ago after a Pat Metheny show. I imagine a gig with Metheny to be life-changing for many musicians. Suddenly, you're touring the world, getting high exposure and good money for 200+ shows a year. Then the next project doesn't involve you. No doubt the exposure is good and leads to new things. But is there no expectation that you stay "part of the band"?

In this case, you were the "victim" (and ultimately beneficiary) of Red Rodney's memory lapse. I guess there can be multiple reasons, from the musical (bandleader "not hearing a trumpet" for this project), to financial reasons (tour didn't make its money and quintet must become quartet), to simple personality clashes. And sometimes the sideman launches their own career thanks to the exposure with the star.

I'm sure many would be interested to hear your take on the good (and the bad!) ways bandleaders inform their band members they are now surplus to requirements.

That's some story. I have studied with Garry for some time now, teaching the Banacos method. Brilliant pianist, great human being.